By Erik M. Francis, M.Ed., M.S.

One of the popular vs. that has made the rounds is doing projects vs. project-based learning. Project-based learning is considered to be “good” – or rather, teaching and learning that should be promoted in the classroom. Doing projects is regarded as “bad” or a learning experience that has little merit or value.

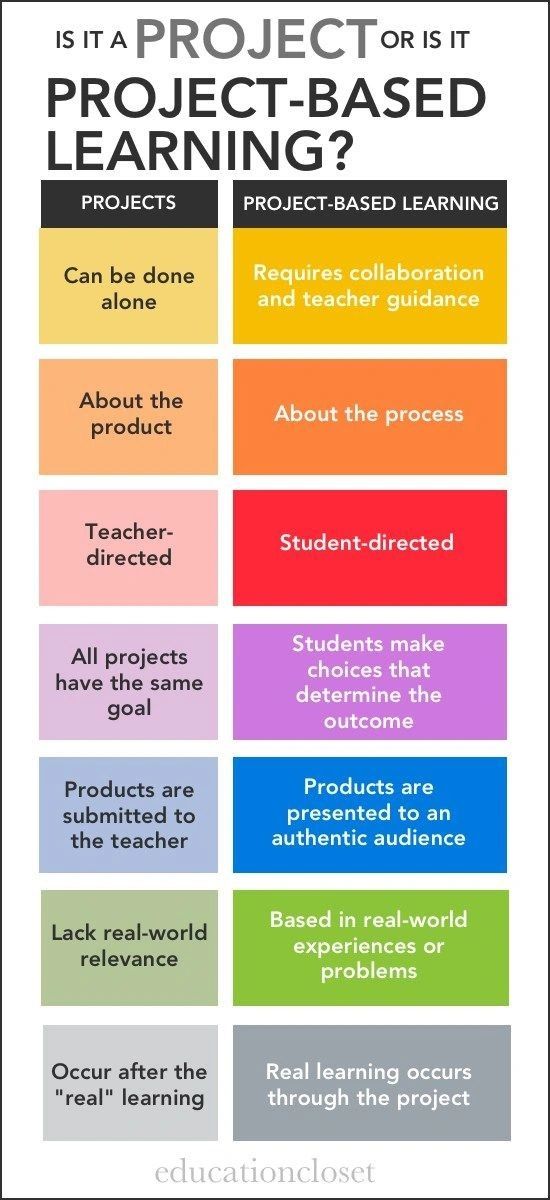

Just look at this graphic that clearly delineates between doing projects and project-based learning. There is truly nothing wrong with this graphic. It clearly distinguishes the differences between the learning experiences of doing projects and project-based learning. It’s also less biased than many of the graphics. However, I have seen other visuals floating around on the internet and presented at conferences with the images for doing projects are presented as black, white, and gray while the ones associated with project-based learning are more colorful.

Just look at this graphic that clearly delineates between doing projects and project-based learning. There is truly nothing wrong with this graphic. It clearly distinguishes the differences between the learning experiences of doing projects and project-based learning. It’s also less biased than many of the graphics. However, I have seen other visuals floating around on the internet and presented at conferences with the images for doing projects are presented as black, white, and gray while the ones associated with project-based learning are more colorful.

While this visual clearly advocates for teaching and learning through project-based learning than doing projects, it is very straightforward and does not seem to have an agenda or slant like the other images out there that compares doing projects vs. project-based learning. However, the message is clear – teaching and learning experiences that have students doing projects are “bad” but those that engage students in project-based learning is “good”.

The discussion over doing projects and project-based learning should not be about which one is “good” or “bad”. It’s actually a comparison between product vs. process. Doing projects is about producing a product that reflects or represents a student’s talent and thinking. Project-based learning is the process of designing something – a plan, product, or procedure – that will address, handle, resolve, or settle an issue, problem, or situation. The project is not the end product produced but rather the activity or task of addressing or responding to an issue, problem, or situation.

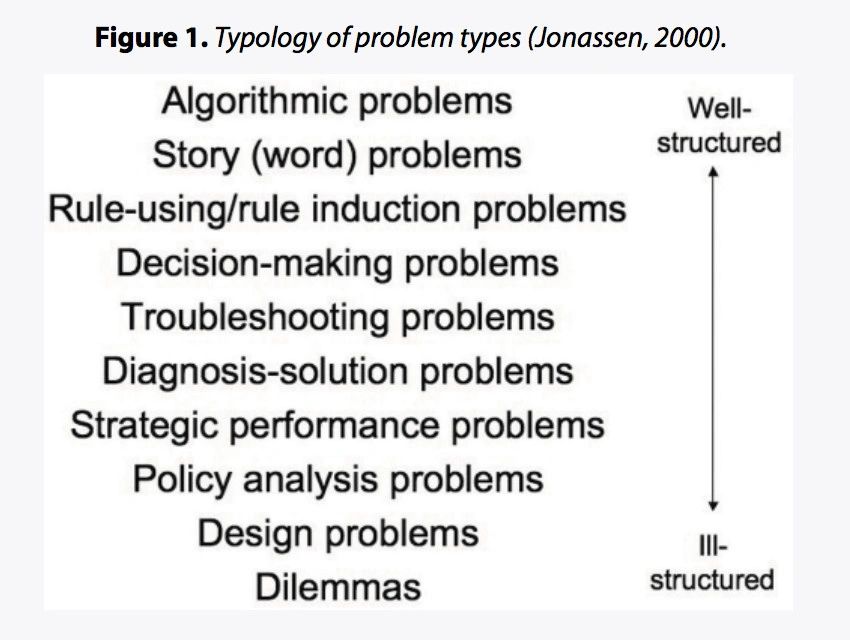

This makes project-based learning actually more synonymous with the other PBL in education – problem-based learning. The Center for Teaching Excellence of Cornell University defines problem-based learning as “a student-centered approach in which students learn about a subject by working in groups to solve an open-ended problem”. The processes and stages of both PBLs are practically the same. The difference is the goal. With problem-based learning, the goal is to solve the problem. With project-based learning, the end result is to design or develop a project that will solve the problem. David H. Jonassen (2000; with Hung, 2008) developed a Taxonomy of Problems that identifies and scaffolds different types of problems based upon their complexity.

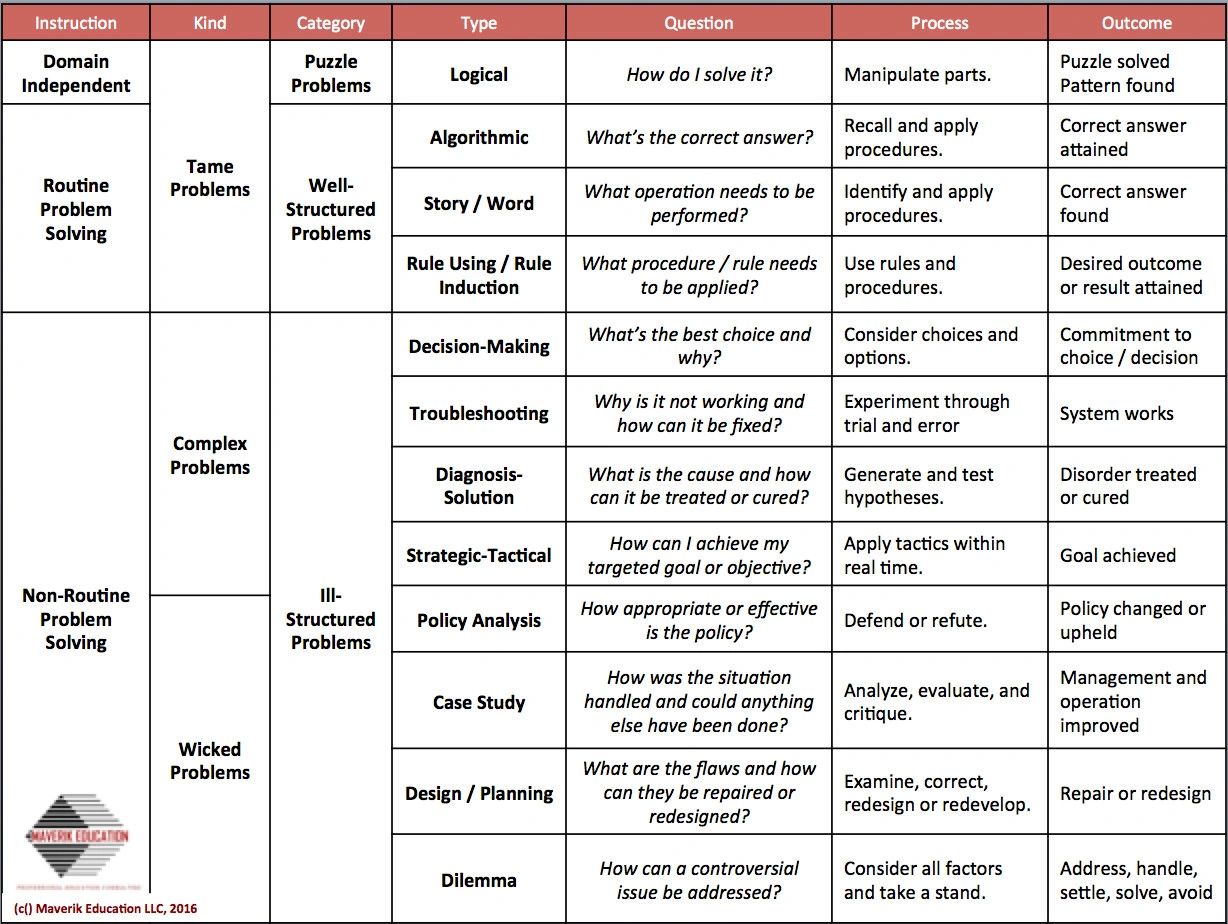

I further expanded upon Johnassen’s Taxonomy of Problems (2000) by creating the following chart categorizing teaching and learning with problems under three different categories:

• Domain-Independent: Tame puzzle problems that have a specific outcome or result but require no background knowledge or foundational understanding in an academic area

• Routine: Tame, well-structured problems that have a specific answer, outcome, or solution and require background knowledge and foundational understanding in an academic area or subject to solve.

• Non-Routine: Ill-structured problems that are complex (there might be more than one possible solution or way to solve them) or wicked (these problems cannot be solved – only addressed, handled, resolved, settled, or even avoided).

These problems can serve the scenarios, settings, and situations in project-based learning. What distinguishes these learning experiences is the context and outcome. Tame problems have an expected result or solution that is either correct or incorrect. Complex problems have alternatives and options both in the process and solution, and students must make choices and defend their decisions. Wicked problems have so many factors and opinions involved that it is extremely difficult to come up with a solution that will be universally accepted. Wicked problems are often considered to be impossible projects because there are so many components, issues, and even obstacles. However, impossible projects are the greatest opportunity for demonstrating and communicating creative thinking – making desires and dreams practical and real. Wicked problems and impossible projects are what put us on the moon, helped us cure diseases, and encourage us to grow and develop socioeconomically and socioemotionally.

So what is the true difference between the two PBLs? If the goal and process involve developing and demonstrating deeper learning to address or respond to a circumstance, issue, or situation, then it’s problem-based learning. If the outcome or result involves going through a design process to develop something – a plan, a policy, a procedure, a product, a proposal – to address or respond to the problem, then it’s project-based learning.

However, that would require doing a project, wouldn’t it?

If project-based learning involves doing projects as part of the process, why is doing projects regarded as “bad”?

It’s most likely because doing projects is considered to be a traditional instructional method, and in modern times, traditional teaching and learning have become synonymous with bad. Doing projects is similar to doing math – it is typically teacher-driven, results-based, and generally not transferrable. Project-based learning is more student-centered, process-oriented, and contextual. It also naturally involves students developing and demonstrating all four C’s of modern learning: critical thinking and problem-solving, creativity and imagination, collaboration, and communication (P21 Council, 2011). Project-based learning presents students with a scenario or situation in a driving question. They are challenged to think critically about how to address or respond to the situation. They are encouraged to collaborate with others – be it their classmates or people with expertise – to address or solve the problem. They are also expected to communicate throughout the process by asking and answering questions; detailing their efforts and findings; and sharing not only their results but also the evidence and reasoning behind them. The fourth C – creativity – engages students to consider alternatives and options and also come up with their own ideas, methods, or ways to address and respond to the problem or situation. The experience students have in project-based learning not only teaches them factual, conceptual, and procedural knowledge but also the essential skills they will use professionally and personally throughout their lives.

It’s also usually not a deeper learning experience – or, at least, not as deep as project-based learning. Yes, students are demonstrating thinking at the highest level of Bloom’s Revised Taxonomy by creating. However, what students are actually doing is expressing themselves creatively. They may be designing, developing, drawing, and dancing, but they don’t know or can’t explain what they did, how they did it, and why they did it the way they did. Doing projects may be creative, enjoyable, and even fun, but in all honestly, it’s a shallow learning experience.

The teaching experience of doing projects is also usually not enjoyable for the adults. Teachers often become overwhelmed not only with creating the activities associated with the projects as well as the grading. Parents often become frustrated with having to arrange schedules so their children can participate with their group to do the project. Sometimes the parents need to purchase the materials needed to design the product. The students don’t make it any easier when they wait until the last minute to do the project or design something that they or even their parents don’t consider to be a quality product. The parents end up doing the project for the student and have it turn it into the teacher as their work. That creates a conundrum for the teacher, who knows the parent did the project – not the child – but they cannot prove it nor do they want to risk making such an accusation.

However, most kids not only find doing projects to be enjoyable but also memorable.

Think about your own experience in grades K-12. What do you remember? Do you remember that lecture your teacher gave, that worksheet you had to do, that test you took, or the project you created and perhaps worked on with your classmates? Along with the extracurricular activities in which we participated and the social experiences we had, what we typically remember about our K-12 education are the projects we did. These were considered to be the “fun” learning experiences – the ones in which we were allowed to design scale models, draw posters, or do dramatic presentations (e.g. acting, dancing, singing) about the concepts and ideas we were learning. Our teachers would then have us present our projects to the class, post them around the room, or plan events in which we could showcase our work.

That’s the greatest benefit of doing projects – it’s personally rewarding. The student feels a sense of pride having their work showcased and even shown off for everyone to see and praise. It also allows students to think like an artisan, which is one of the mindsets Thomas Friedman and Michael Mendelbaum suggest students should develop and demonstrate as a “creative creator” or “creative server”. Artisans describe people who make things or provide services “with a distinctive touch and a flair in which they took personal pride” (Friedman & Mandelbaum, 2012). When students think like an artisan, they take pride in what they do – and that’s what doing projects allow our students to do.

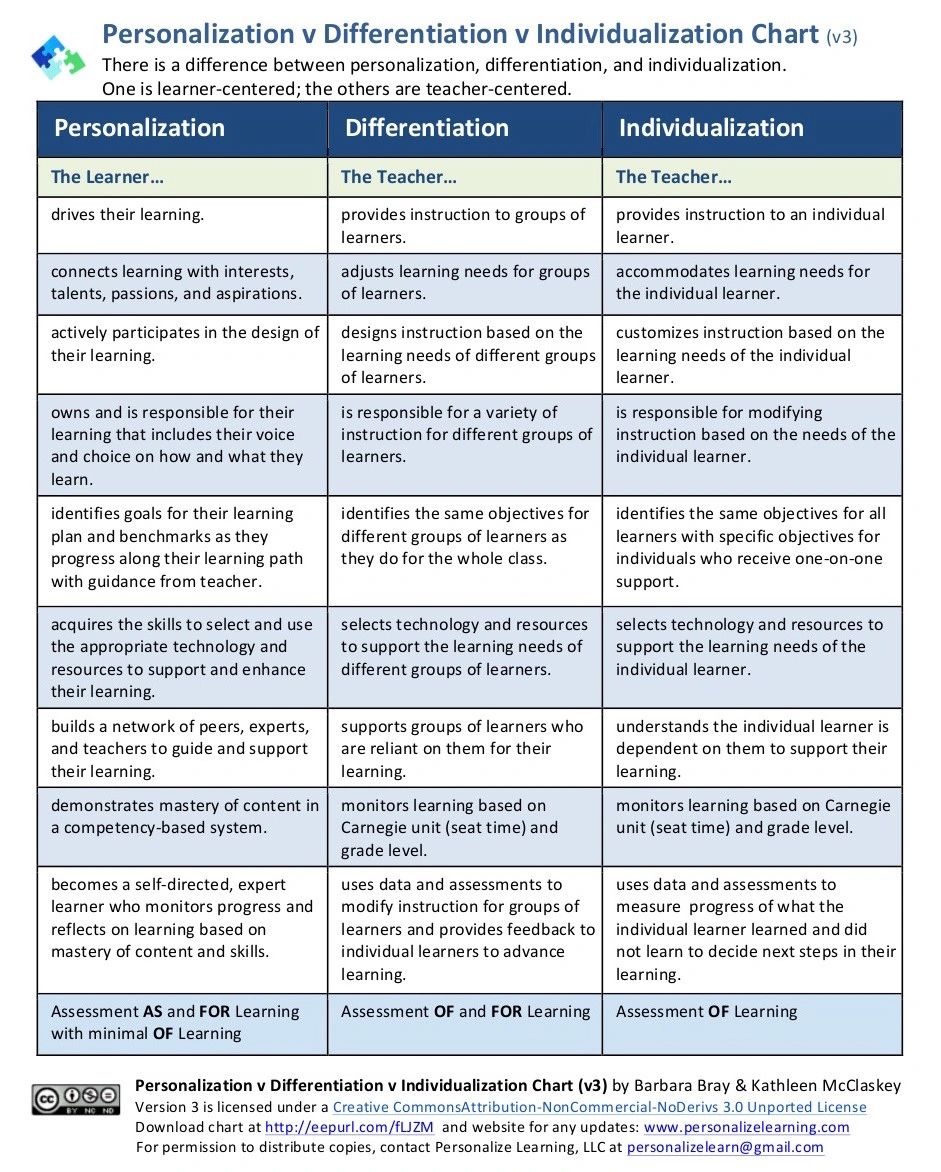

Doing projects also foster teaching and learning for differentiation and individualization, and personalization. Doing projects differentiates instruction by allowing teachers to utilize multiple ways students can demonstrate and communicate their learning. Doing projects also individualizes instruction in that it focuses on how an individual student processes and presents the learning they have acquired and developed. Doing projects also personalizes learning by encouraging students to express and share their learning in their own unique way rather than simply do the same task or take a standardized assessment.

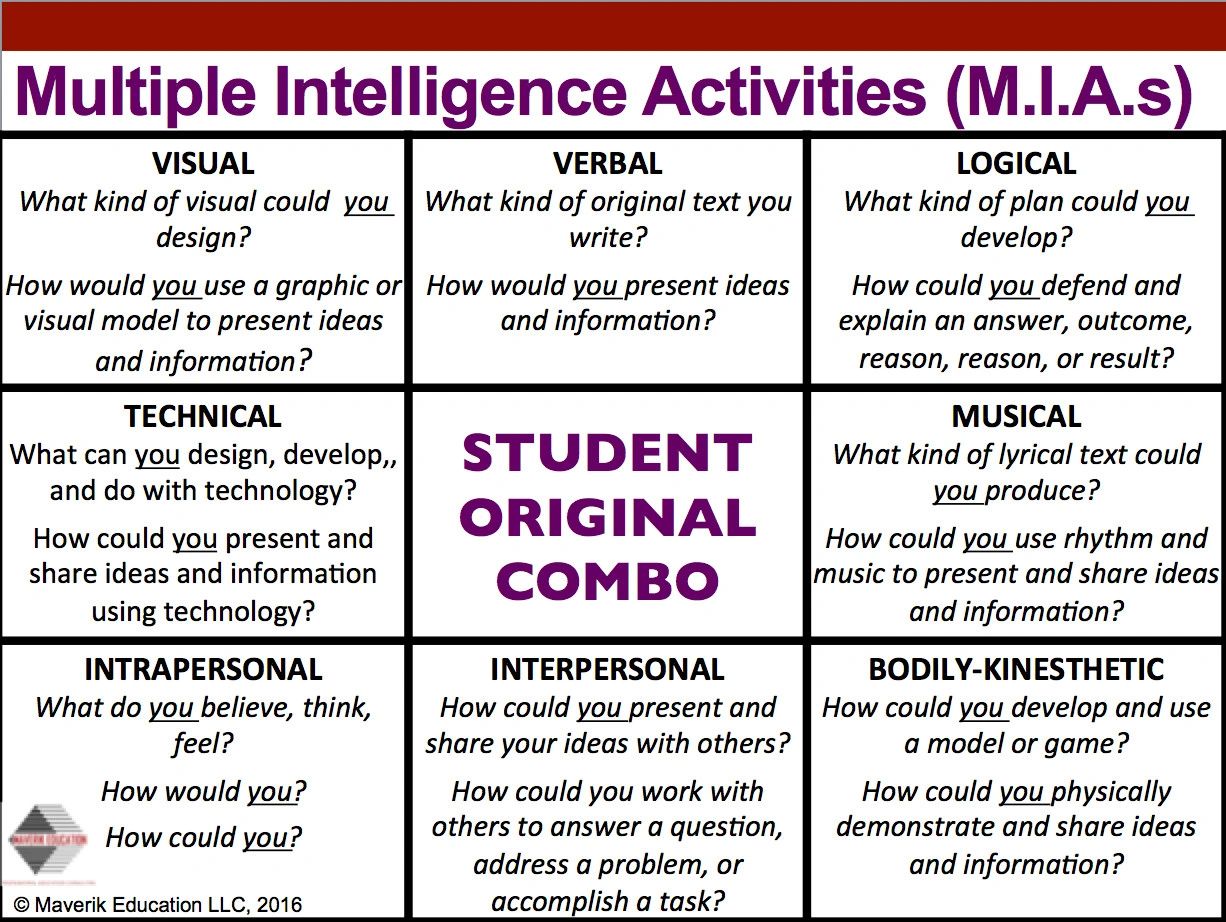

To promote differentiated and individualized instruction and personalized learning by doing projects, I designed the Multiple Intelligence Activity (M.I.A.) Grid. Each square within the grid addresses a specific strength or skill identified in Howard Gardiner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligence. The students are presented with a driving good question that asks them how could or would you or what can you design, develop, or do? The project itself is broad yet targeted to the specific intelligence, catering to the students’ strength and skill. For example, under visual/spatial, students may be asked what kind of visual or what kind of sequential art could you design.

Student choice is a key component for doing projects. The M.I.A. Grid promotes student choice by allowing students to choose which project they want to do. Instead of giving them the same project to do, students can choose from a menu of options that challenges and engages them in developing and demonstrate their talent and thinking through design. In the center of the grid is a square called Student Original Combo that allows students either to combine the project choices presented (e.g. write a story and turn it into a video) or come up with their own project that would address the objective and essential question of the unit. This not only further encourages students to choose how to demonstrate and communicate their learning but also think creatively about what kind of project could they personally come up with that addresses the text or topic they are learning.

The teaching and learning experience with the M.I.A. Grid also encourages students can to develop and demonstrate the other 4 C’s of modern learning. Students should be allowed to choose whether they work collaboratively with a classmate or do their project alone (collaboration). They should be able to demonstrate and communicate how their project addresses the goal or objective or the unit (critical thinking). They should also be required to detail how they researched, developed, and designed their project and present it to the class (communication). Inevitably, the goal of the M.I.A. chart is not only for students to do a project but also go through and document the process in which they designed and developed their project – and that’s project-based learning.

Inevitably, active student-centered learning experiences will have students doing projectsand engaging in project-based learning. The issue should not be doing projects vs. project-based learning. The question should be should students do a project so they can express and share their learning creatively or should students develop and demonstrate their talent and thinking by addressing and responding to a problem through a project-based learning experience?

Why not both?

This article was originally posted on August 26, 2018.

Erik M. Francis, M.Ed., M.S. is an author, educator, and speaker who specializes in teaching and learning that promotes cognitive rigor and college and career readiness. He is also the author of Now THAT’S a Good Question! How to Promote Cognitive Rigor Through Classroom Questioning published by ASCD. He is also the owner of Maverik Education LLC, providing academic professional development and consultation to K-12 schools, colleges, and universities on developing learning environments and delivering educational experiences that challenge students to demonstrate higher order thinking and communicate depth of knowledge.

Find Erik here on MyEdExpert.