Rethinking the Opening Minutes

Suzy Pepper Rollins

Ahhh…the opening minutes of class. Students file in like they’ve spent days trudging through the desert, begging for water, swearing they need to have an IV started. A stream of elaborate stories about homework ensue, accompanied by pleas to visit their lockers and perhaps call their attorneys. The office needs something, attendance has to be entered…and a colleague requires just one second with you at the door.

Thank goodness for warm-ups! Largely a classroom management tool, these get students out of the halls, into their desks and busy so that the business side of education can be handled.

But wait! What if these “get them busy warm-ups” turn out to be just about the opposite of what thirsty learners really need? Because the case can be made that the opening minutes might just be the best time to learn. Are we maximizing this critical instructional time?

The Case for a Different Start to Learning

This is not a case against getting students started immediately – that’s certainly a sound practice. Rather, this is a case for a different, more elevated type of task to get thinking started. Consider this:

- Students remember the most from the opening minutes of class. Their brains are fresh and open for learning.

- Motivation to learn begins in the opening minutes. Students’ brains are asking: Is this going to be valuable? Are my chances good for success? The opening minutes should set up the new concept and instill in students, “This is going to be really interesting and I think I can do it!”

- 20 minutes of warm-ups x 180 days of school = 60 hours. Yikes! Sixty hours of instruction is so valuable…every minute counts!

- Learning largely involves attaching new information to prior knowledge. Opening minutes can enable students to pull critical files out of their brains, pad their knowledge a bit, and be ready for new learning!

Strategies for the Beginning of a Learning Episode

In both of my books, I call these “Success Starters,” to encapsulate their mission. Here are characteristics I strive for. An opening task should:

- Be highly engaging – every student will jump right in

- Spark intellectual interest for learning the new concept

- Get students questioning, collaborating, and tapping into prior knowledge

- As much as possible, connect to students’ worlds

For example, in a literacy lesson I teach about the cotton gin, I first begin with an opener in which students make decisions about how cell phones have changed our society and economy. After they go to town on that, I put a picture of the cotton gin up. “Now, let’s talk about a different invention.” Students have to determine which of these two inventions changed the world more. It’s relevant (student love those phones!), engaging, sparks thinking, and connects to prior knowledge. And I can still check attendance. If I began this lesson with “Let’s learn about the cotton gin…” Well, we can predict the outcome.

Facts and Fibs are one of my favorite openers for all content areas, including math. Placed on strips, pairs discuss and position the strips as they arrive at a consensus, explaining their reasoning. For example, if students were introduced to exponents the prior day, this Fact/Fib might be just the ticket to get the lesson started:

Fact or Fib? Exponents

A number raised to a power is multiplied times itself repeatedly.

A number raised to the power of 1 is equal to 1.

When an exponent is negative, you have to subtract.

A base raised to a negative exponent creates a fraction with 1 as the numerator.

A number raised to a power is added repeatedly.

Make it Visual

Visual representations can also be an engaging start to learning. Pictures of earthquakes, the Dust Bowl, magnets, battlefields, or onomatopoeia can provide concrete images of what will be discussed today. Rather than have students sit and watch; however, they must connect and respond to the pictures. If it’s angles, what’s different about them? The Great Depression: what do you see in their faces? Early computers: What’s changed?

Make it Wow

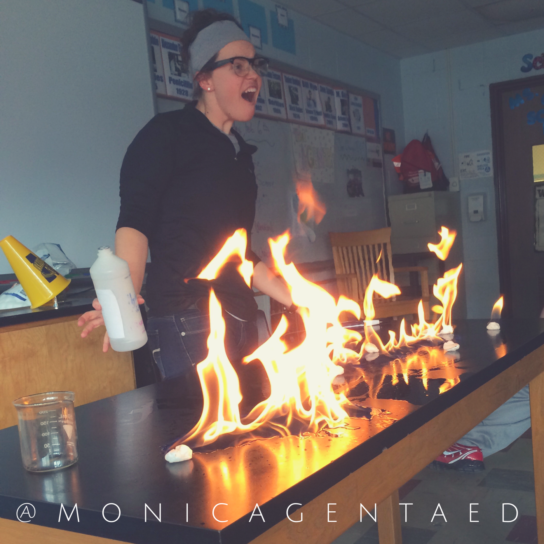

Author, presenter, and science teacher Monica Genta takes the “wow” factor of the opening minutes to the next level. “During my astronomy unit, I bring outer space to my students. What better way to do this than lighting a table on fire. Right?” She uses cotton balls as stars and isopropyl alcohol as nuclear fusion – these flaming spheres of hot glowing gas demonstrate the size, color, and temperature for various stars. “As kids walk through the door on the first few days of the unit they are completely mesmerized by the real-life demo.” #betheblueapple

Get Learners Thinking

Angela Stockman, author and ELA consultant, doesn’t start literal fires; instead, she has a focus on lighting up student thinking. She believes in the power of student reflection in the opening minutes, rather than traditional warm-ups. She pitches a prompt, and either has students turn and talk or craft responses in their notebooks. For primary writers, she encourages metacognition about their writing with this process:

- Look at your writing

- Put a smiley face next to a part where you were thinking hard

- Circle a part of your writing that makes you proud

Make it Real

Math consultants and authors Dr. Dianne DeMille and Jennifer Munoz strive for real-world relevance in opening minutes, which they consider “appetizers” for the main meal. Students can gather data sets from newspapers and magazine articles to introduce mean, median, mode, range, and quartiles. Next, students create number lines, tables, and histograms to represent the data. Studying ratios? An example might be from the local fast food drive through. Utilize what matters to learners– be it in the layout of their rooms, the stores they frequent, or the shows they watch.

So, let’s banish those bland warm-ups! Instead, let’s get students thinking, talking, and interacting with the content right away…not minutes later. Rather than send the message of “sit down and get busy,” let’s create opening tasks that say, “Today is going to be a fabulous, highly engaging day of learning!”

From article published on EdCircuit.com. To read complete article: